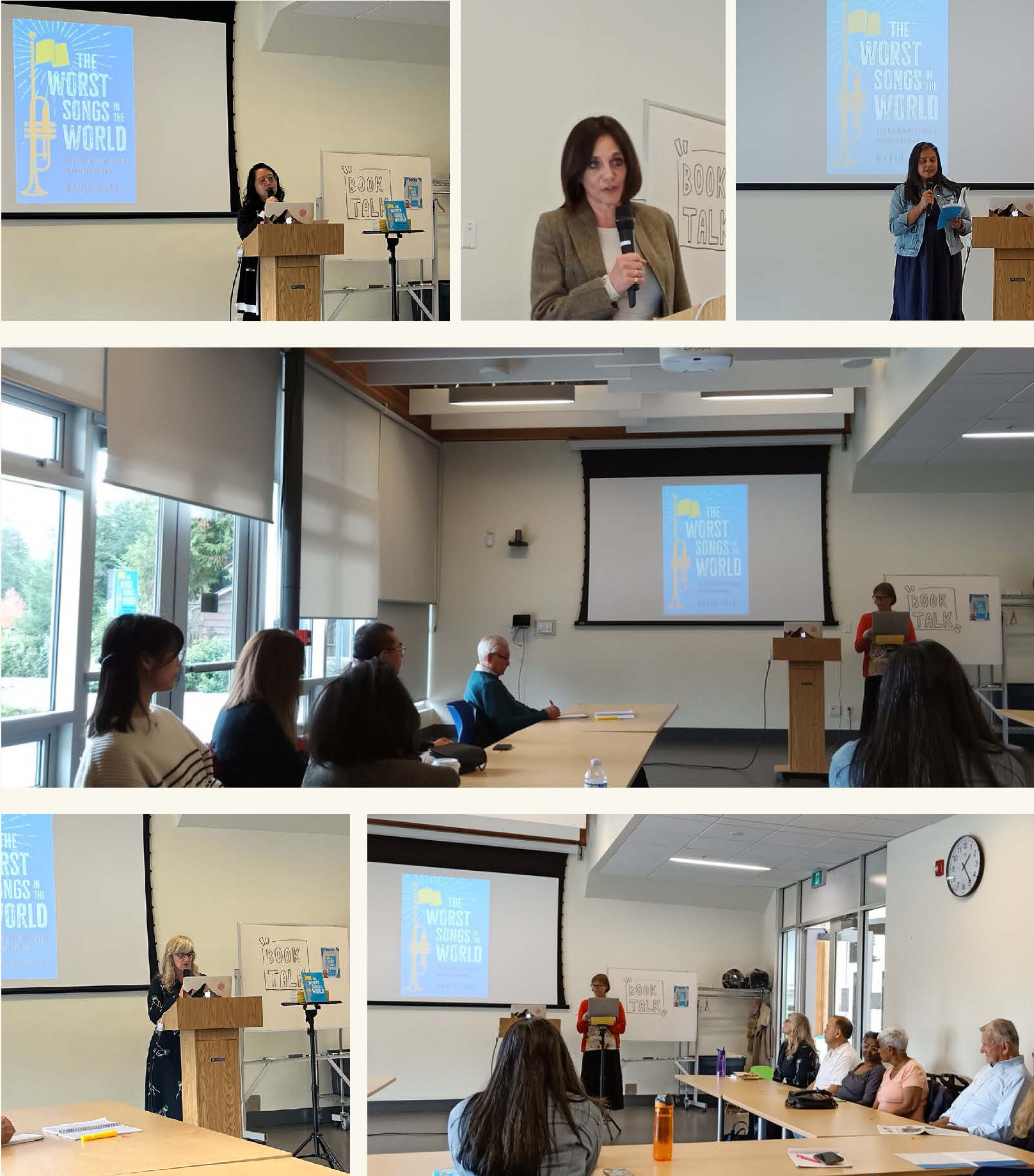

A UNA Book Talk event was held on the last Saturday afternoon of October in the Social Room of the Wesbrook Community Centre.

A small group of residents gathered to talk about a new book with a unique perspective on songs we all know well: national anthems.

The book was The Worst Songs in the World – The Terrible Truth About National Anthems, written by the late journalist and author David Pate, published this year by Dundurn Press.

The event was moderated by Jennifer Chen, a member of The Campus Resident’s Editorial Committee who was also a personal friend of Pate. The late author, who was born in Glasgow, Scotland and died last February in Nova Scotia, was a reporter, editor, and broadcaster in Ireland before spending the rest of his career in Canada with the CBC.

This event featured four reviews and personal reflections presented by UBC professor Emilie K. Adin, Vancouver Island University instructor Heather Bell, writer, editor and writing instructor Taslim Jaffer, and reporter/writer Paula Arab.

Paula Arab shared Pate’s concern that national anthems should be gender neutral, noting the change in Canada’s anthem from “in all thy sons command” to “in all of us command” in 2018. Gendered language in anthems is common, as Arab noted, sharing that her Lebanese father reminded her that the Lebanese anthem speaks only of “stalwart men.” Arab’s father settled in Montreal in the 1950s and although it was struggle, she said he found a sense of belonging singing the national anthem at Montreal Canadiens hockey games.

And that is where many people become familiar with national anthems, as they are almost always a feature at sporting events.

Heather Bell referred to a portion of Pate’s book that describes the history of national anthems as performed at the Olympic Games.

Bell cited Pate’s writing on the Olympic decision to have a lyric-less, instrumental playing of national anthems during the games. In making that decision, it was argued that tunes and melodies develop feelings of purpose and unity. This result was in keeping with the Olympic Charter which states: “Olympic Games are competitions between athletes in individual or team events and not between countries.” In that regard, Bell also noted that the Games are awarded to cities, and not countries.

In her review, Taslim Jaffer noted David Pate’s reference to colonial, paternalistic, white supremacist attitudes expressed through a controversial incident half a decade ago when in Jaffer’s native Kenya, a British company placed a copyright on the country’s national anthem. The incident prompted a national outcry and led to efforts to amend the country’s copyright laws.

Jaffer also appreciated Pate’s reference to an incident when Disney corporation was accused of cultural appropriation. The Swahili phrase “Hakuna Matata” – which roughly means “no worries” – is spoken daily in Kenya and neighbouring African countries, but was also used in Disney’s 1994 movie, The Lion King. Following the movie’s release, the company had the phrase trademarked and has since used it in their licensed merchandise, a move which drew condemnation around the world.

At one point in his book, Pate commends Australia’s “Recognition in Anthem Project”, which was developed to address the glaring absence of any reference to the people who were the original inhabitants of that country.

As he points out, the “Recognition in Anthem Project” was not just about changing one word. In the words of Aboriginal Australian Deborah Cheetham, “It’s saying, ‘Who are we? What have we achieved? Where are we going?’ We can’t capture the spirit of this nation one word at a time.”

Book talk moderator Emilie Adin said she is using Pate’s findings in her own unpublished essay on ethnic and national identity.

At the completion of the four presentations, Rebecca Pate, the late author’s daughter, spoke to the group in a Zoom video recording. She said her father had hoped to write his next book on national flags.

The host concluded the event by inviting questions and comments.

As someone assigned to report about this book on national anthems, I spoke about my experience as a singer of the Canadian and American anthems at sporting events and how they are received by fans.

I recalled singing a bilingual version of our national anthem at a baseball game in Winnipeg. When I switched to the French portion, my wife told me she noted how a man near her turned toward his wife, nodding his appreciation.

It was emotional responses like these which helped encourage Pate to explore and dig deeper into the meaning of these songs in his book. And to do so, he reached out to many experts, including Michael Dean of the University of California in Los Angeles.

In an interview with the professor and classical singer, Dean told Pate: “The reason music is such an integral part of human existence is because notes, melodies, harmonies, and rhythms that we associate with certain events in our experiences go into our brains,”

“Music works on the brain in a way that almost no other thing does, which is why people who have dementia can still play instruments or can still recognize songs.”

But as Pate argues, national anthems, while striking a chord and evoking intense personal and often positive feelings, need to be looked at in a new light. And he puts forth a compelling argument in The Worst Songs in the World.

Instead of “cutting throats, watering fields with blood, building walls with the bodies of enemies, and celebrating the sound of machine guns”, he thought we should all be demanding better national songs.

WARREN MCKINNON IS A LONGTIME CAMPUS RESIDENT.